Paderborn-Neuenbeken

Catholic Church St. Mary, Roncalliplatz 2

Paderborn-Neuenbeken, Catholic Church St. Mary, exterior view from the northeast. Photo: LWL/Dülberg.

Paderborn-Neuenbeken, Catholic Church St. Mary, interior view towards the northwest. Photo: LWL/Dülberg.

Paderborn-Neuenbeken, Catholic Church St. Mary, wall painting, Devil with Cowhide beneath The Last Supper, Photo: LWL/Dülberg.

Paderborn-Neuenbeken, Catholic Church St. Mary, wall painting, Deposition of Christ. Photo: LWL/Dülberg.

Paderborn-Neuenbeken, Catholic Church St. Mary, wall painting, Standing Mother of God. Photo: LWL/Dülberg.

Paderborn-Neuenbeken, Catholic Church St. Mary, wall painting, The Last Supper, detail of the central group with Christ and the Apostles John and Judas. LWL/Dülberg.

Paderborn-Neuenbeken, Catholic Church St. Mary, wall painting, Deposition of Christ, right-hand section with Nicodemus, John and the Bad Thief. Photo: LWL/Dülberg.

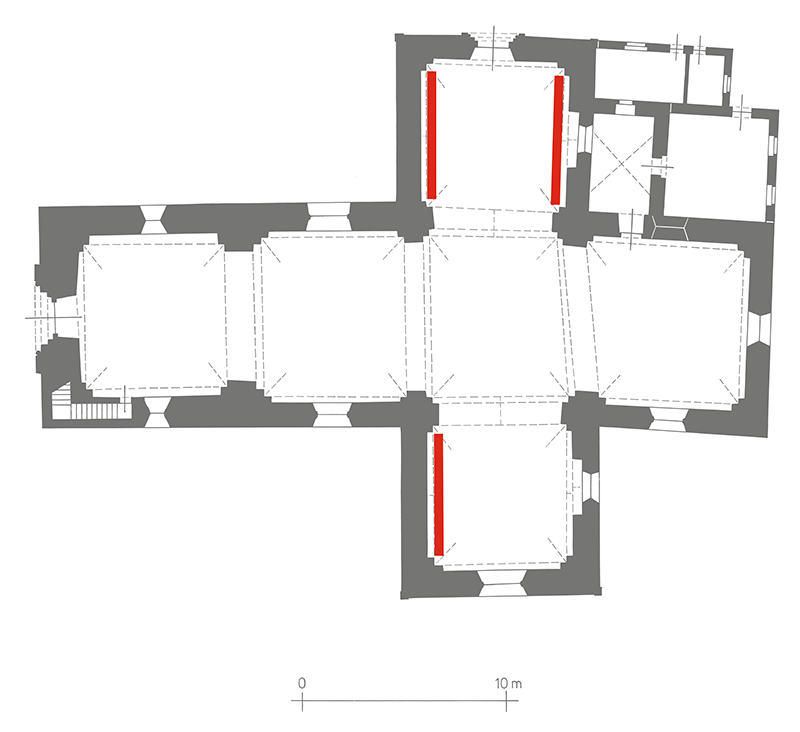

Paderborn-Neuenbeken, Catholic Church St. Mary, ground plan (The mappings (German version) can be opened by clicking on the red markings).

Building structure

The church, laid out in the shape of an isosceles cross with a straight closed choir, protruding transept and single-bay central nave is extended in its interior to a Latin cross by the opened tower bay in the width of the central nave.

Building data

Beginning of 13th century. Dating of the once extended east-facing vestry unknown. Modern extension to the north of the vestry.

Romanesque polychrome architectural decorations

Against the white wall and vault areas, the pillars and arches painted in a greenish grey form the framework for the filigree scrolling vine frieze in grey and red with ochre-coloured and red accompanying ribbons that cover the space like a decorative net and emphasise its plastic elements. On a level with the impost scrolling vine friezes are draped around the wall areas that run below for formerly smaller window apertures. On the east walls of the transept and choir the painted flanking columns are still preserved that probably ornamented the windows in the whole room. Towards the transept the broad white areas on the soffits of the transversal arches in the middle are ornamented with frieze strips made of rising grey trails of hearts, the transversal arches in the central nave and those leading to the choir are decorated with delicate wavy scrolling vines.

Contrary to the usual style in the “Westphalian painting system“, the groins in Neuenbeken are not omitted and accompanied by bands but emphasised precisely on the arris. Wavy scrolling vines in the crossing and southern transept and vines of hearts alternating with scrolling vines in the north transept run along the arris and are emphasised by coloured accompanying strips. All vault arches are painted on their face-ends in continuation of the pillar colour scheme with green ashlars, the white joints of which were originally omitted and showed the ground of white wash.

Since the exposure of the polychrome architectural decorations in 1964 the transept vaults have been given back their ornamentation with large tree-of-life motifs in the vault caps.

Figurative Romanesque wall painting

North transept, east wall, top: single figure of a Prophet; below: Mother Mary as the remnant of a crucifixion.

North transept, west wall: The Last Supper, below it the remains of a painting: Devil with Cowhide.

Southern transept, west wall: Deposition of Christ.

Crafting technique/painting technique

Lime fresco painting on compacted single-layer plaster. A lime-slurry was applied to the still damp plaster and then one to two layers of white lime-wash were added. The incisions and the preparatory drawing were carried out in the fresh lime-wash. The shadow areas of the faces and limbs and all ochre-coloured parts of the garments were first painted in yellow ochre. After this, iron-oxide red parts of the garments, the contours of the bodies and fine inner drawings of the nose, mouth and eyes were outlined very skilfully and fast with iron-oxide red. This was finally completed with black contours, the drawing of the pupils and the elaboration of the toes.

There was doubtless delicate ochre-coloured or red preparatory drawing in some parts in order to determine the position of the ochre-coloured shadings, but this is hardly recognisable.

The black contours, inner drawings and inner colouring are no longer preserved today as they were applied last and have not bonded well with the lime-wash. The white highlights are formed by omitted areas that show the light lime-wash. That is the most outstanding feature of the painting technique in Neuenbeken. This applies, moreover, to the ornamental bands which indicates a simultaneous creation of the polychrome architectural decorations and the figurative paintings.

The colour scheme is restricted mainly to earth colours such as yellow ochre, green earth and vine black. Gildings or plastic applications, for example of the halos, do not exist.

Conservation history

The figurative wall paintings were exposed for the first time in 1864/65 and exposed once again in 1922 and painted over in historicising manner. In 1964 exposed again and carefully restored without coloured reintegrations, this was repeated in 1984 and 2010.

The backgrounds of the paintings in the transept were completely white. The painting therefore lay like a coloured water-colour on the white lime-wash. For this reason the appearance of the paintings is reduced by losses in the secco parts that had not bonded well, but not so drastically as is the case in those Romanesque paintings that originally showed precious, strongly coloured backgrounds in blue and green and where today at the best the grey underpainting of the picture backgrounds can be seen, for example in St. Nicholas’ Chapel in Soest.

The figure of the Prophet on the east wall of the north transept shows dark-brown remains on contours from the 19th century that partly lie over the original black contours. But they follow the original lines.

The east cap of the choir vault today shows a reproduction of Christ in Majesty from the year 2009 in neo-Romanesque style, which has been applied over the covered, original fragments.

Description and iconography

Of the originally presumed 14 individual figures on the sides of the windows (six in the choir, four in the transept, four in the nave) only the Prophet on the east wall of the north transept is still visible. He is standing with his right leg slightly bent and frontally facing the observer, his stretched out arms showing his titulus. He is holding it with his left hand, it extends diagonally across the chest of the Saint as far as his right arm that he is lifting in an indicating gesture. It is possible that he is pointing out a pictorial action in the unpreserved stained-glass painting to his right, but more likely it is supposed to be indicating the message on the titulus that was originally legible.

Of the figure of Mary further below on the east wall, only the head, a part of the upper body and a piece of her garment have been preserved. Mary is laying her left hand on her cheek in a gesture of melancholy. This position of her hand, together with her look of bereavement and facing towards the upper right, is based on a long illustrative tradition in depictions of the Crucifixion. For this reason it can be presumed that the figure belonged to a crucifixion that is not preserved.

The Last Supper on the west wall of the north transept shows Christ and the Disciples at a long table. Christ is sitting in the middle of the picture and is looking down at the observer. He has taken his favourite Disciple John, who is much smaller and is portrayed as being almost childlike, onto his lap. John is turning pensively to the left and is resting his head on his arm. The other eleven Apostles are engaged in conversation with gesticulating hands, each in two groups of two at the ends of the table and the remaining three as a group around Christ are turned towards him. As a result of Christ giving bread to Judas and passing it to him across the table, without looking at him, the middle group is extended downwards to the 13th Apostle, the betrayer of Christ, who can be seen in a cowering position in front of the table, receiving the bread with tilted head and opened lips. His right-hand is stretched out as if he wished to thank Christ, and his left hand, hidden from the view of the others, is clasped around a no longer recognisable object, perhaps a fish.

In the fragment of the pictorial scene below the The Last Supper one can recognise two devils and three women. The women are kneeling at the lower edge of the picture and are decently clothed in light, ankle-length garments and hood-type headdresses with barbettes. Behind and also above him there are two devils who are busy pulling a cloth or rather a cowhide apart, whereby the devil on the left is spreading out hide by its corners, the devil at the top is bending down over it or rather leaning and handling on it. He is probably writing, but this is no longer recognisable today. In the case of the women these are probably the type that chat in church. Behind their backs the devil is noting this sin on the cowhide. The content of the representation can be interpreted as being a warning against a long record of sins during the Last Judgment.

As a counterpart to the depiction of the Last Supper, on the south wall of the southern transept there is a representation of the Deposition of Christ. Here, too, the figures are set on a lime-washed plaster ground and are standing without any further framing on the light surface of the wall. Probably in order to fill the area better, besides the usual figures belonging to the Deposition of Christ, the composition has been extended by the two robbers from the Crucifixion. Since 10th century Mary and John have always been depicted in the Deposition of Christ, even if they are not mentioned in the gospels. In all four scripts, on the other hand, Joseph of Arimathea is named as being a fair man (see Matthew 27). Only in the Gospel of St. John, Nicodemus is additionally mentioned as a disciple (Jo 19,39). The situation, in which Joseph of Arimathea takes Christ down from the cross, is described particularly vividly in Neuenbeken. As a sign of his reverence he covers his hand with the linen cloth that he has laid around his shoulders. As in the Apostles of the Last Supper, his fingers grip the cloth in a lively manner and thus stabilise the hips of the Son of God. The other hand holds his body further below where today a large section of the picture is missing. The bonding of Christ and Joseph is unique: Following the left hand that is already released from the cross, the body has been lowered with the armpit resting on the head of the helper and, together with the hair of Joseph, forms a mutual, curved contour line.

Art-historical classification

Correlating style features of all the figurative representations are: Omitted areas of the plaster ground at the seams, modelling of joints, emphasising of volume, liveliness in the position of hands, variations in headdress and hands. In the case of the Last Supper the gripping of the garment fabric and also the way the fabric falls around limbs, feet and hands is particularly characteristic, in the case of the Deposition of Christ the placing of the hair on the forehead that extends in a very varied manner as far as the shaggy strands of hair in the case of the Bad Thief. The warping seams (seam frills) and also the decorative borders with painted trim of precious stones on the stockings of the Prophets, can also be found in the scenic representations on the transept, just like the ornamental border on the garment of the left-hand Apostle in the Last Supper and the folds in the garments of the figures standing alongside with more simple garments in the figures of the Deposition of Christ.

In the existing examples of Romanesque wall paintings in Westphalia, the topics of the figurative scenes are unique, the quality of their workmanship excels by far the usual decoration of a village church. The quality of the paintings and ornamentation on omitted lime-wash that has been applied on still damp plaster ground, lead the observer to presume the origin of all the paintings immediately after completion of construction. The simple building shapes, with pointed arches only being used in the transept, can be dated at the beginning of the 13th century. Newly discovered parallels to various high-quality book illustrations from the same period concur with the technical findings of the paintings and support a dating of the paintings at the time of construction which so far had been set at about 30 years after the building completion. The great significance of this monument lies in the unity of polychrome architectural decorations, figurative paintings and building structure as well as the special quality of the scenic depictions.

The chronological classification leads us to ask about the training of the wall painters who were engaged in Neuenbeken. At the beginning of 13th century one can expect the performance of painters not affiliated to an order, who were engaged in various places and scriptoria and gained experience there and certainly also collected patterns, as the research into book illustrations has assumed for some years. The mixture of various characteristics that were effectively applied in Neuenbeken, here again leads us to assume such secular artists who were trained with illuminated manuscripts in various centres in the Thuringian-Saxon and Lower Saxon region and show slightly differing handwritings. With this a first step into the research and classification of the wall paintings in Neuenbeken to the environment of numerous contemporary illuminated manuscripts has been ventured which others were later to follow.

Dating

Around 1210 (at the same time as the polychrome architectural decorations from the time of construction).